Stale-While-Nah

"There are only two hard things in Computer Science: cache invalidation and naming things."

Hello there! Kenji here, back for another round of shared learning and exploration. If you caught my introductory post, “Hello Web (with reservations)” you know I’m embarking on this slightly uncomfortable but utterly intriguing journey of personal blogging. The goal? To dig into the nuances of web technologies, especially as AI steps into the spotlight, and to hopefully make sense of it all, together.

And speaking of making sense of things, there’s an old joke, often attributed to Phil Karlton, that goes: “There are only two hard things in Computer Science: cache invalidation and naming things.” Some might add a third: “off-by-1 errors.” Well, it seems we’ve stumbled upon a delightful combination, as a recent observation reminded me just how challenging cache invalidation (of mental models!) can be, especially when an old concept gets stuck in folks’ brain. The web keeps evolving, and awareness and dissemination of up-to-date knowledge is hard.

Brain-cache-control: max-age=yes

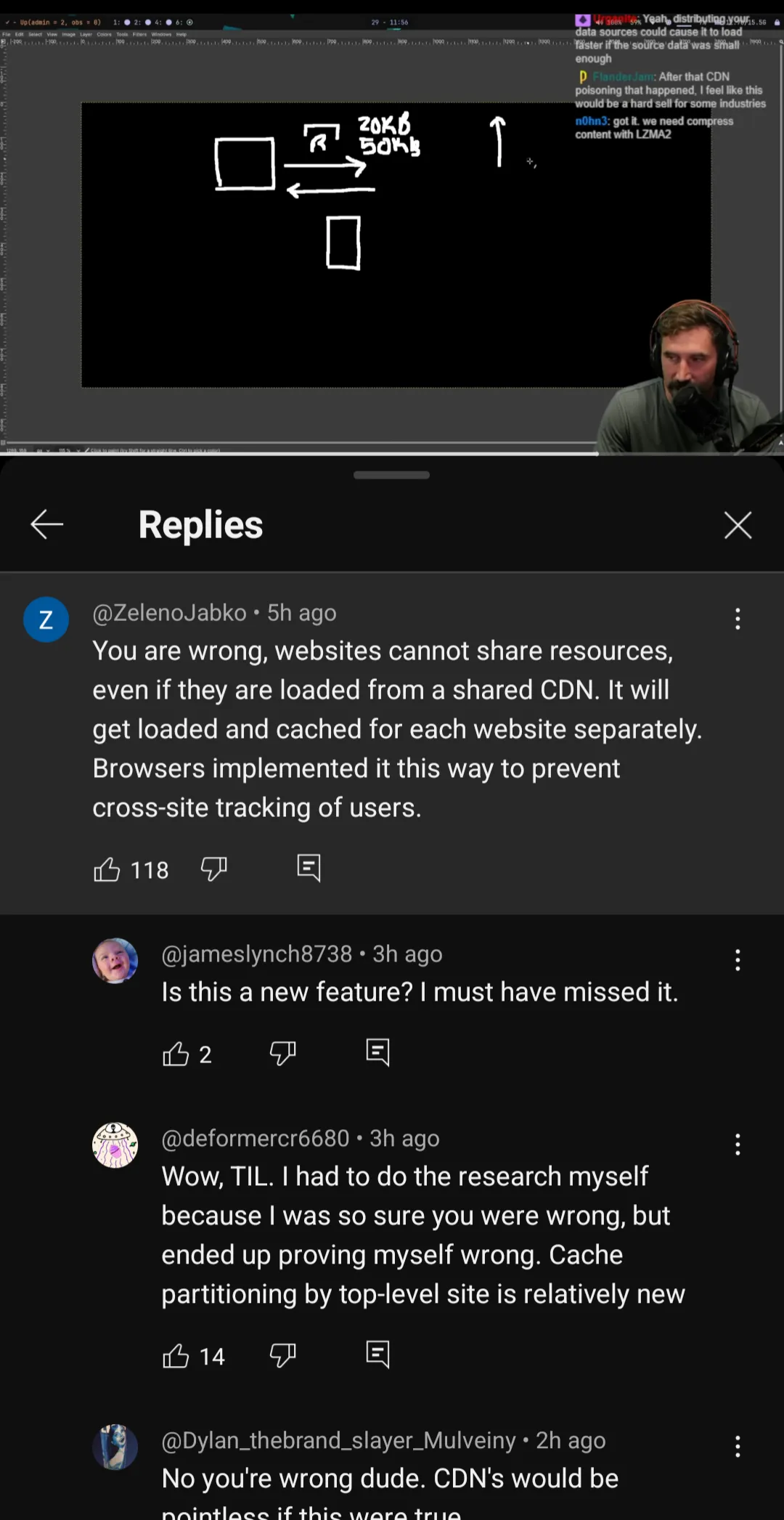

That very “stuck in brain cache” moment happened a few days ago. I was catching up on YouTube and caught a segment from ThePrimeTime. Since the video popped up in my feed and was about loading performance – a topic deeply ingrained from my previous role on the Chrome team – I naturally had to watch it. As is my habit, I jumped into the comments section to gauge reactions and pinpoint key moments. It was there that I quickly noticed a recurring thread of discussion around the HTTP cache misconception.

The Unicorn of Web Speed

The discussion touched on a common thought: could widely used libraries, like a 40-kilobyte zipped React, be cached by browsers from CDNs and then reused across different websites? The idea, naturally, is to save bandwidth and speed things up. It’s a very understandable hope! The desire to leverage shared resources to make the web faster is something many inherently gravitate towards.

"... resources have long been isolated across sites due to HTTP Cache Partitioning."

However, as someone who spent a good chunk of time on the Chrome team’s web platform loading, my internal alarm bells gave a gentle, knowing ding. I saw comments echoing similar sentiments about HTTP cache and resource sharing across origins, and it just reinforced a subtle but significant detail: resources have long been isolated across sites due to HTTP Cache Partitioning. What genuinely surprised me was seeing such widespread confusion around a change implemented in Chrome around five years ago, and even longer in other browsers like Safari (way back in 2013). The comment section itself became a live demonstration of this “stuck in brain cache” phenomenon: while some folks correctly pointed out the updated browser behavior, others, equally confidently, retorted with “what’s the point of CDN then?”

The Stale-While-Nah Reality

It seems an older understanding of how browser caches work was still firmly embedded in the collective “brain cache”—a classic case of stale-while-nah, where the assumption is that one’s understanding of the platform is evergreen (max-age=2147483648 which works out to about 68 years, and the largely symbolic immutable attribute). Thus, no revalidation is ever needed for these mental models.

The World Weird Web days

When the web was still largely nascent, browser caches were like a single, grand public library. Every website visited by a user would check out web resources from this one shared collection. If site-A.com needed a popular JavaScript library from some-cdn.com/library.js, it typically ends up stored in this central library. Then, when site-B.com wanted the exact same version from the exact same URL, the browser simply directed site-B.com to reuse any existing and fresh copy from the central library. No need to download it again!

Sounds like pure performance optimization, right? And for a long time, it was seen that way. This cross-site sharing meant reduced bandwidth, faster page loads, and general web efficiency. Many performance optimizations and CDN strategies were built around this implicit assumption. However, while the concept of shared web resources sounds impactful, realizing significant practical benefits is remarkably complex. It often requires a perfect alignment of many conditions rarely met in the wild, and even then, the primary gains aren’t always in raw page load times. That’s a deep dive for another time, perhaps!

Why we can’t have nice things

But this seemingly straightforward win for performance came with a hidden cost -– a significant privacy flaw. Think of it as a subtle side-channel that undermined how browsers isolate different websites from each other. A malicious site-A.com could infer your browsing habits or even sensitive information. How? By observing if certain CDN resources (which might only be loaded by specific other sites like mybank.com, myweirdspace.com or whistleblowerwiki.com) were already present in your browser’s cache. By timing how long it took to load these resources, site-A.com could infer whether you had recently visited mybank.com, for instance. This kind of “cache probing” could be used for anything from building a profile of your browsing history to attempting cross-site tracking.

Everybody gets a book shelf!

HTTP Cache Partitioning was introduced to close this privacy loophole. Instead of one giant shared public library, think of it now as if every single website gets its own, completely separate, private mini-library within your browser. Even if site-A.com and site-B.com request the exact same resource from the exact same URL, each site receives and stores its own distinct copy within its own private library. This means that while a resource might still be ‘on the shelf’ in site-A.com’s private library, it will not be reused by site-B.com, even if it’s the identical resource. A malicious website can no longer peek into your browsing habits across different sites by observing what’s been ‘checked out’ from a shared space.

In practice, it’s slightly more complex than what I’ve described, because of cross-origin iframes shenanigans, so feel free to delve deeper into the technical specifics and motivations.

When stale models go mental

Now, this isn’t a critique of ThePrimeAgen or anyone else. Instead, I see this example as a powerful illustration of a much broader, more universal challenge in our tech world: the difficulty of effective knowledge transfer and the persistence of outdated or incomplete information.

"The web is a powerful and ubiquitous platform, and its continued success absolutely hinges on all of us regularly revalidating our mental models to ensure a fresh, up-to-date understanding of how it works best."

While yet another blog won’t solve the problem, maybe it will help a few folks. More importantly, it helps me because it’s a forcing function to get hands-on and write about it. Those are powerful tools to gain clarity and reflect on how we can empower developers to build truly great and helpful user experiences.

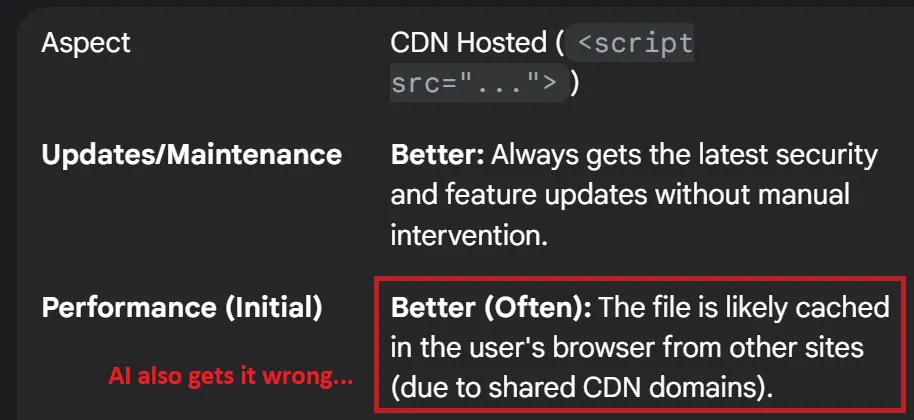

The HTTP cache partitioning example, in its own small way, perfectly encapsulates why this shared learning is so critical. The web is a powerful and ubiquitous platform, and its continued success absolutely hinges on all of us regularly revalidating our mental models to ensure a fresh, up-to-date understanding of how it works best. This challenge may even be exacerbated in the future, as AI-generated code, if trained on obsolete or subpar practices, could inadvertently perpetuate or amplify these very misconceptions!